Indonesian architecture

Indonesian architecture reflects the diversity of cultural, historical and geographic influences that have shaped Indonesia as a whole. Invaders, colonisers, missionaries, merchants and traders brought cultural changes that had a profound effect on building styles and techniques. Traditionally, the most significant foreign influence has been Indian. However, Chinese, Arab—and since the 18th and 19th centuries—European influences have been important.

Religious architecture

The Prambanan temple complex.

Although religious architecture has been widespread in Indonesia, the most significant was developed in Java. The island's long tradition of religious syncretism extended to architecture, which fostered uniquely Javanese styles of Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic, and to a lesser extent, Christian architecture.

A number of often large and sophisticated religious structures (known as candi in Indonesian) were built in Java during the peak of Indonesia's great Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms between the 8th and 14th centuries. The earliest surviving Hindu temples in Java are at the Dieng Plateau. Thought to have originally numbered as many as 400, only 8 remain today.

The Dieng structures were small and relatively plain, but architecture developed substantially and just 100 years later the second Kingdom of Mataram built the Prambanan complex near Yogyakarta; considered the largest and finest example of Hindu architecture in Java. The World Heritage-listed Buddhist monument Borobudur was built by the Sailendra Dynasty between 750 and 850 AD, but it was abandoned shortly after its completion as a result of the decline of Buddhism and a shift of power to eastern Java. The monument contains a vast number of intricate carvings that tell a story as one moves through to the upper levels, metaphorically reaching enlightenment. With the decline of the Mataram Kingdom, eastern Java became the focus of religious architecture with an exuberant style reflecting Shaivist, Buddhist and Javanese

influences; a fusion that was characteristic of religion throughout Java.

"Grand Mosque" of Yogyakarta shows javanese interpretation and took Hindu heritage of Meru stepped roofs.Although brick was used to some extent during Indonesia's classical era, it was the Majapahit builders who mastered it, using a mortar of vine sap and palm sugar. The temples of Majaphit have a strong geometrical quality with a sense of verticality achieved through the

use of numerous horizontal lines often with an almost art-deco sense of streamlining and proportion. Majapahit influencess can be seen today in the enormous number of Hindu temples of varying sizes spread throughout Bali . Several significant temples can be found in every village, and shrines, even small temples found in most family homes. Although they have elements in common with global Hindu styles, they are of a style largely unique to Bali and owe much to the Majapahit era.

By the fifteenth century, Islam had become the dominant religion in Java and Sumatra, Indonesia's two most populous islands. As with Hinduism and Buddhism before it, the new religion, and the foreign influences that accompanied it, were absorbed and reinterpreted, with mosques given a unique Indonesian/Javanese interpretation. At the time, Javanese mosques took many design cues from Hindu, Buddhist, and even Chinese architectural influences (see image of "Grand Mosque" in Yogyakarta). They lacked, for example, the ubiquitous Islamic dome which did not appear in Indonesia until the 19th century, but had tall timber, multi-level roofs not that dissimilar to the pagodas of Balinese Hindu temples still common today.

A number of significant early mosques survive, particularly along the north coast of Java. These include the Mesjid Agung in Demak, built in 1474, and the Al-Manar Mosque in Kudus (1549) whose

menara ("minaret") is thought to be the watch tower of an earlier Hindu temple. Particularly during the decades since Indonesian independence, mosques have tended to be built in styles more consistent with global Islamic styles, which mirrors the trend in Indonesia towards more orthodox practice of Islam.

Traditional vernacular architecture

An avenue of houses in a Torajan village. Rumah adat are the distinctive style of traditional housing unique to each ethnic group in Indonesia. Despite this the diversity of styles, built by peoples with a common Austronesian ancestry, traditional homes of Indonesia share a number of characteristics such as timber construction, varied and elaborate roof structures, and pile and beam construction that take the load straight to the ground.

These houses are at the centre of a web of customs, social relations, traditional laws, taboos, myths and religions that bind the villagers together. The house provides the main focus for the family and its community, and is the point of departure for many activities of its residents. Traditional Indonesian homes are not

architect designed, rather villagers build their own homes, or a community will pool their resources for a structure built under the direction of a master builder and/or a carpenter.

Traditional house in Nias; its post, beam and lintel construction with flexible nail-less joints, and non-load bearing walls are typical of rumah adat. The norm is for a post, beam and lintel structural system with either wooden or bamboo walls that are non-load bearing.

Traditionally, rather than nails, mortis and tenon joints and wooden pegs are used. Natural materials - timber, bamboo, thatch and fibre - make up rumah adat. Hardwood is generally used for piles and a combination of soft and hard wood is used for the house's upper non-load bearing walls, and are often made of lighter wood or thatch. The thatch material can be coconut and sugar palm leaves, alang alang grass and rice straw.

Traditional dwellings have developed to respond to natural environmental conditions, particularly Indonesia's hot and wet monsoonal climate. As is common throughout South East Asia and the South West Pacific, Indonesian traditional vernacular homes are built on stilts (with the notable exceptions of Java and Bali). A raised floor serves a number of purposes: it allows breeze to moderate the hot tropical temperatures; it elevates the dwelling above stormwater runoff and mud; allows houses to be built on rivers and wetland margins; keeps people, goods and food from dampness and moisture; lifts living quarters above malaria-carrying mosquitos;

and the house is much less affected by dry rot and termites.

A traditional Batak house in North Sumatra.

A fishing village of pile houses in the Riau archipelago.

Many forms of rumah adat have walls that are dwarfed in size by large roof—often of saddle shape—which are supported independently by sturdy piles.

Over all traditional styles, sharply inclined allowing tropical rain downpours to quickly sheet off, and large overhanging eaves keep water out of the house and provide shade in the heat. The houses of the Batak people in Sumatra and the Toraja people in Sulawesi (tongkonan houses) are noted for their stilted boat-shapes with great upsweeping ridge ends. In hot and humid low-lying coastal regions, homes can have many windows providing good cross-ventilation, whereas in cooler mountainous interior

areas, homes often have a vast roof and few windows.

Some of the more significant and distinctive rumah adat include:

* Batak architecture (North Sumatra) includes the boat-shaped jabu homes of the Toba Batak people, with dominating carved gables and dramatic oversized roof, and are based on an ancient Dong-Son model.

* The Minangkabau of West Sumatra build the rumah gadang, distinctive for their multiple gables with dramatically upsweeping ridge ends.

* The homes of Nias peoples include the omo sebua chiefs' houses built on massive ironwood pillars with towering roofs. Not only are they almost impregnable to attack in former tribal warfare, but flexible nail-less construction provide proven earthquake durability.

* The Riau region is characterised by villages built on stilts over waterways.

* Unlike most South East Asian vernacular homes, Javanese rumah adat are not built on piles, and have become the Indonesian vernacular style most influenced by European architectural elements.

* The Bubungan Tinggi, with their steeply pitched roofs, are the large homes of Banjarese royalty and aristocrats in South Kalimantan.

* Traditional Balinese homes are a collection of individual, largely open structures (including separate structures for the kitchen, sleeping areas, bathing areas and shrine) within a high-walled garden compound.

* The Sasak people of Lombok build lumbung, pile-built bonnet-roofed rice barns, that are often more distinctive and elaborate than their houses.

* Dayak people traditionally live in communal longhouses that are built on piles. The houses can exceed 300 m in length, in some cases forming a whole village.

* The Toraja of the Sulawesi highlands are renowned for their tongkonan, houses built on piles and dwarfed by massive exaggerated-pitch saddle roofs.

* Rumah adat on Sumba have distinctive thatched "high hat" roofs and are wrapped with sheltered verandahs.

* The Dani of Papua live in small family compounds composed of several circular huts known as honay with thatched dome roofs.

Palace architecture

Sultan palace in Yogyakarta.

Istana (or "palace") architecture of the various kingdoms and realms of Indonesia, is more often than not based on the vernacular adat domestic styles of the area. Royal courts, however, were able to develop much grander and elaborate versions of this traditional architecture. In the Javanese Kraton, for example, large penodopos of the joglo roof form with tumpang sari ornamentation are elaborate but based on common Javanese forms, while the omo sebua ("chief's house") in Bawomataluo, Nias is an enlarged version of the homes in the village, the palaces of the Balinese such as the Puri Agung in Gianyar use the traditional bale form, and the Pagaruyung Palace is a 3-storey version of the Minangkabau Rumah Gadang.

Similar to trends in domestic architecture, the last two centuries have seen the use of European elements in combination with traditional elements, albeit at a far more sophisticated and opulent

level compared to domestic homes.

In the Javanese palaces the pendopo is the tallest and largest hall within a complex. As the place where the ruler sits, it is the focus of ceremonial occasions, and usually has prohibitions on access to this space.

Colonial architecture

Javanese and neo-classical Indo-European hybrid villa. Note the Javanese roof form and general similarities with the Javanese cottage (pictured in gallery).

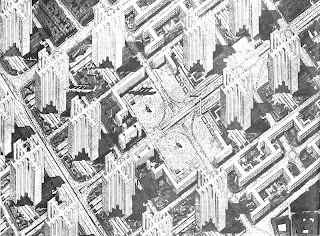

The 16th and 17th centuries saw the arrival of European powers in Indonesia who used masonry for much of their construction. Previously timber and its by-products had been almost exclusively used in Indonesia, with the exception of some major religious and palace architecture. One of the first major Dutch settlements was Batavia (later Jakarta) which in the 17th and 18th centuries was a fortified brick and masonry city.

For almost two centuries, the colonialists did little to adapt their European architectural habits to the tropical climate. In Batavia, for example, they constructed canals through its low-lying terrain, which were fronted by small-windowed and poorly ventilated row houses, mostly in a Chinese-Dutch hybrid style. The canals became dumping grounds for noxious waste and sewage and an ideal breeding ground for the anopheles mosquitos, with malaria and dysentery

becoming rife throughout the Dutch East Indies colonial capital.

Ceremonial Hall, Bandung Institute of Technology, Bandung, by architect Henri Maclaine-Pont

Although row houses, canals and enclosed solid walls were first thought as protection against tropical diseases coming from tropical air, years later the Dutch learnt to adapt their architectural style with local building features (long eaves, verandahs, porticos, large windows and ventilation openings).

The Indo-European hybrid villas of the 19th century would be among the first colonial buildings to incorporate Indonesian architectural elements and attempt adapting to the climate. The basic form, such as the longitudinal organisation of spaces and use of joglo and limasan roof structures, was Javanese, but it incorporated European decorative elements such as neo-classical columns around deep verandahs. Whereas the Indo-European homes were essentially Indonesian houses with European trim, by the early 20th century, the

trend was for modernist influences—such as art-deco—being expressed in essentially European buildings with Indonesian trim (such as the pictured home's high-pitched roofs with Javan ridge details).

Practical measures carried over from the earlier Indo-European hybrids, which responded to the Indonesian climate, included overhanging eaves, larger windows and ventilation in the walls.

This pre-war Bandung home is an example of 20th century Indonesian

Dutch Colonial styles

.At the end of the 19th century, great changes were happening across much of colonial Indonesia, particularly Java. Significant improvements to technology, communications and transportation had brought new wealth to Java's cities and private enterprise was reaching the countryside.[2] Modernistic buildings required for such development appeared in great numbers, and were heavily influenced by international styles. These new buildings included train stations, business hotels, factories and office blocks, hospitals and education institutions. The largest stock of colonial era buildings are in the large cities of Java, such as Bandung, Jakarta, Semarang, and Surabaya.

Bandung is of particular note with one of the largest remaining collections of 1920s Art-Deco buildings in the world,[3] with the notable work of several Dutch architects and

planners, including Albert Aalbers, Thomas Karsten, Henri Maclaine-Pont, J Gerber and C.P.W. Schoemaker.

Colonial rule was never as extensive on the island of Bali as it was on Java— it was only in 1906, for example, that the Dutch gained full control of the island—and consequently the island only has a limited stock of colonial architecture. Singaraja, the island's former colonial capital and port, has a number of art-deco kantor style homes, tree-lined streets and dilapidated warehouses.

The hill town of Munduk, a town amongst plantations established by the Dutch, is Bali's only other significant group of colonial architecture; a number of mini mansions in the Balinese-Dutch style still survive.

The lack of development due to the Great Depression, the turmoil of the Second World War and Indonesia's independence struggle of the 1940s, and economic stagnation during the politically turbulent 1950s and 60s, meant that much colonial architecture has been preserved through to recent decades. Although colonial homes were almost always the preserve of the wealthy Dutch, Indonesian and Chinese elites, and colonial buildings in general are unavoidably linked with the human suffering of colonialism, the styles were often rich and creative combinations of two cultures, so much so that the homes remain sought after into 21st century.

Native architecture was arguably more influenced by the new European ideas than colonial architecture was influenced by Indonesian styles; and these Western elements continue to be a dominant influence on Indonesia's built environment today.

Post independence architecture

National Monument (Monas) at Merdeka square,Jakarta.

Early twentieth century modernisms are still very evident across much of Indonesia, again mostly in Java. The 1930s world depression was devastating to Java, and was followed by another decade of war, revolution and struggle, which restricted the development of the built environment. Further, the Javanese art-deco style from the 1920s became the root for the first Indonesian national style in the 1950s. The politically turbulent 1950s meant that the new but

bruised Indonesia was neither able to afford or focussed to follow the new international movements such as modernist brutalism.

Continuity from the 1920s and 30s through to the 1950s was further supported Indonesian planners who had been colleagues of the Dutch Karsten, and they continued many of his principles.

"Let us prove that we can also build the country like the Europeans and Americans do because we are equal"

— Sukarno

Istiqlal Mosque, the national mosque of Indonesia.

Despite the new country's economic woes, government-funded major projects were undertaken in the modernist style, particularly in the capital Jakarta. Reflecting President Sukarno's political views, the architecture is openly nationalistic and strives to show the new nation’s pride in itself. Projects approved by Sukarno, himself a civil engineer who had acted as an architect, include:

* A clover-leaf highway.

* A broad by-pass in Jakarta (Jalan Sudirman).

* Four high-rise hotels including the famous Hotel Indonesia.

* A new parliament building.

* The 127 000-seat Bung Karno Stadium.

* Numerous monuments including The National Monument.

* Istiqlal Mosque the largest mosque in Southeast Asia.

The 1970s, 1980s and 1990s saw foreign investment and economic growth; large construction booms brought major changes to Indonesian cities, including the replacement of the early twentieth styles with late modern and postmodern styles.